This is the first of I don't know how many analyses I've written and am going to write, both on my own music and on others'; I certainly want to revise an old essay I wrote on Richard Dawson's harmonic language, write more on tactus modulations in songs (Baths, Dirty Projectors, The Dead Science, and Pretend are on the list), and explain how the Beethoven sample in Pluperfect Mind provided melodic material for the choral section; if you have any other requests or suggestions, pop me a DM/email. I originally wrote this particular analysis when I was contemplating applying for a master's course — which ended up being too daunting of a proposition — but I've since edited it a bit for publishing here. A certain level of knowledge of music theory (time signatures and whatnot) is assumed of the reader, but hopefully it'll be of interest to someone who doesn't mind my navel-gazing.

Black Moon, Lilith begins with repeated piano chords fading in over a manipulated field recording of the London Tube (special prize to whoever's autism allows them to identify which line it is). There’s no rhythm section to contextualise these chords, so the listener latches onto them as an isochronous tactus of around 78 BPM. In other words, the listener feels a beat that is steady enough to perceive as even. Any lags or jolts in the tactus can be mentally ascribed to the tape warp effect, which is especially pronounced in the introductory passage. The bass note changes every two or four chords, so the bar length is probably construed as 2/4.

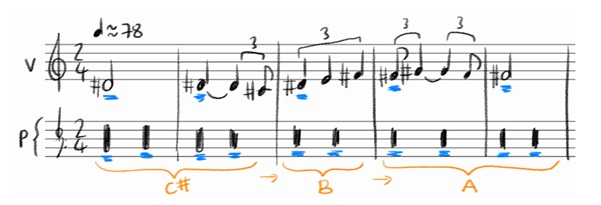

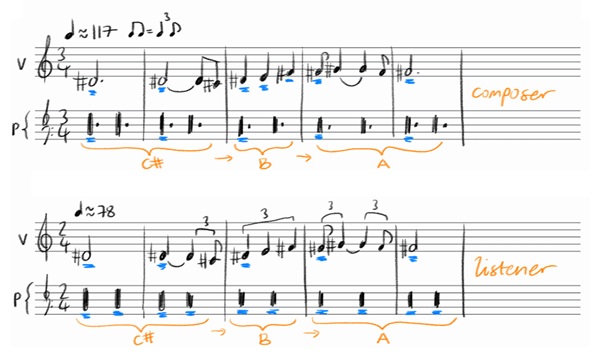

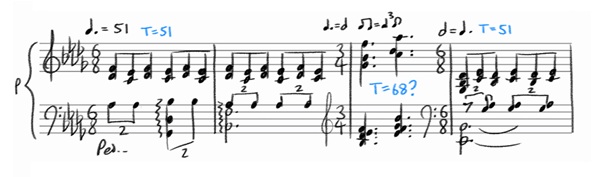

When the vocals enter at 0:19, they don’t do much to challenge this tactus perception, despite some hemiolas between the voice and piano. Here's a diagram of the vocal part and the piano part’s rhythm; blue underlining of notes indicates they land more or less on the tactus, though the vocal part is more often than not off the grid and has been quantised in transcription.

At 0:40, the chords are grouped differently now: the bass note changes every three beats, inviting the listener to adjust and feel the song in 3/4 time instead of 2/4. This is especially strengthened in the final perceived 3/4 bar of the verse, where the vocals emphasise each beat — “insecurities”.

But then something weird happens at 0:50. Remember how, without a rhythm section, we latch onto the bass note of each chord to feel the tactus? Now a new, even lower bass line has appeared, and if we keep feeling the upper chords as the beat, this bass line seems terribly wonky. The listener is left unsure of how to group the perceived beats: is it 2/4 or 3/4? Neither sound quite right anymore, and the piano part looks just as messy.

In fact, the listener’s ears readjust, changing the tactus altogether from c.78 BPM to c.117 BPM. This is a clean 2:3 ratio and gives the feeling of having increased the tempo by 50%. Now the bass line feels rock solid in a distinct [5+4]/4 metre, and the upper chords — which previously acted as our tactus anchor — feel uneven because they are in fact swung. But (surprise!) those upper chords were always swung like this from the very beginning of the song.

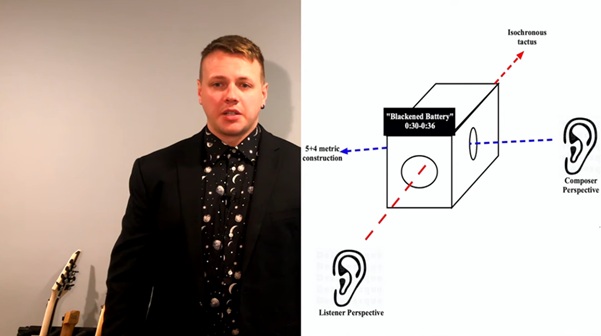

This aural illusion can be explained with the notion of rhythmic parallax, a new approach to analysing rhythmic surfaces devised by Calder Hannan in his 2020 paper for the Society for Music Theory on the song Blackened Battery by Car Bomb. His paper presentation is available on his YouTube channel Metal Music Theory; I encourage you to check it out, along with Car Bomb’s music. Rhythmic parallax is the method by which a rhythmic surface can be intuited and understood from multiple perspectives, whether as a composer, listener, performer or transcriber. In this instance, I as the composer began writing the piano part with one rhythmic perspective — that of swung dotted quarter notes to a faster beat — but then I intuitively “wrote” the vocal part through improvisation on a new rhythmic perspective — that of a slower isochronous tactus — more as a listener/performer.

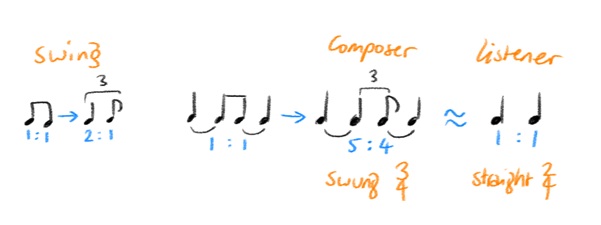

So let’s analyse the swung rhythm and how it could be interpreted as isochronous. There are countless swing ratios in existence, but the classic 2:1 triplet swing will be used here. We can think of the unswung rhythm as a quarter note tied to an eighth note, then an eighth note tied to a quarter note, for a simple 1:1 rhythmic ratio. When we introduce the swing, that ratio shifts to 5:4 (3+2 : 1+3). The faster the tempo, the harder it becomes to distinguish that wonky 5:4 rhythm from the isochronous 1:1 rhythm, especially if there’s no audible subdivision going on. So the composer might hear that constructed 5:4 rhythm that they wrote, but a listener, oblivious to this intention, might hear the isochronous 1:1 rhythm. This 5:4 rhythmic illusion is something that Car Bomb deliberately exploits in their music when they write in fast 9/16 time subdivided as 4+5/16 or 5+4/16; when they switch to 8/16, the tactus feels like it’s sped up, when in fact the time signature has just changed subtly.

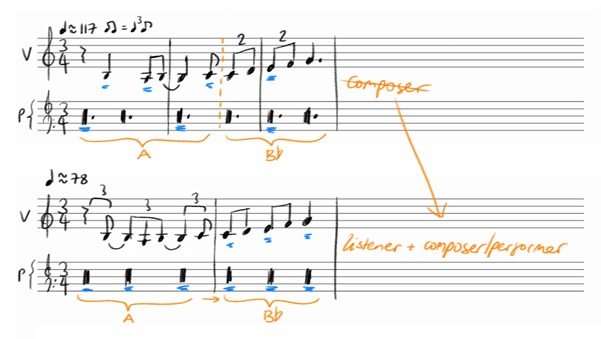

With this in mind, let’s revisit the opening five bars of the first verse: “under an ebbing earth’s shadow”. Here they are, written from the composer’s perspective and the listener’s perspective, with notes falling on the beat underlined in blue. As we can see, both interpretations are sound, but for a listener who’s just heard a series of solo piano chords, there’s little reason for them to interpret those chords as dotted quarter notes in a swung 3/4. If they’re paying close attention, they might hear some wonkiness in the third bar’s hemiola, but would that be enough to destabilise the perceived tactus that’s already been established, especially as the vocals go increasingly off the grid?

And now let’s go back to “of desires and insecurities” again. Look at how everything is grouped together when the previous composer’s perception of swung 3/4 at 117 BPM is applied to this phrase. When you compare it to the listener’s perception of straight quarter notes at 78 BPM, it seems far less elegant. This is because the vocal line wasn’t written out but conceived intuitively by singing along to the piano part. The composer becomes the listener becomes the performer, shifting to a new perception of the rhythmic surface. Rhythmic parallax in action.

When I recorded the piano part, the tactus I was feeling was in fact the consistent pulse of both the verses and choruses: 117 BPM. However, when singing over the verses, I felt a tactus of 78 BPM, the same tactus most listeners would feel. In this way, the movements from verse to chorus and chorus back to verse are examples of what Calder Hannan would call a tactus modulation.

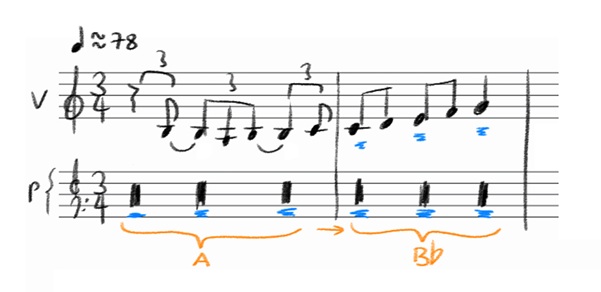

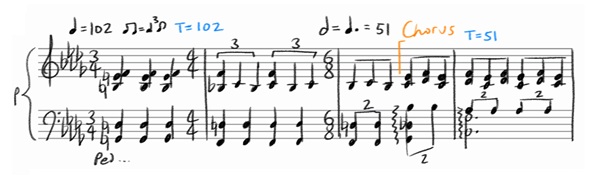

Now for an analysis of Guinefort’s Grave, which presents similar rhythmic concepts in different contextual relations. The song begins in a swung simple time, like the chorus of Black Moon, Lilith, shifting time signature fairly frequently between 3/4, 2/4, and 5/4 (which can be interpreted as [3+2]/4).

From the composer’s perspective, the beat remains consistent at 102 BPM. Entering into the chorus, the time signature changes to 4/4; the left hand articulates the pulse while the right hand plays quarter-note triplets, creating hemiolas. There are no eighth notes in sight to create a swing.

In the middle of the chorus, there is a lone bar of 3/4 which consists of two dotted quarter-note chords. This allows for the first glimpse of swing since the end of the verse.

The chorus ends with the same 3/4 bar in rhythmic preparation for the beginning of the second verse.

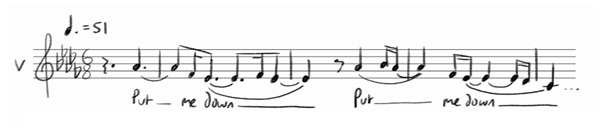

Both verse and chorus have maintained that consistent 102 BPM simple-time tactus. A listener’s perspective, however, is likely to shift to a slower 51 BPM 6/8 tactus at the transition to the chorus. This can happen for a few reasons. The previous tapping 102 BPM pulse is relegated to the middle voice, obscured by the higher triplets and synth bass (not notated here). What’s more, the vocal line’s rhythm supports the 6/8 feel rather than the 4/4 feel. Thirdly — as mentioned before — the swing is absent and no longer able to reinforce the 102 BPM beat as the tactus. The effect is not just the tactus modulating to half-speed, but also from swung simple to compound time.

This new tactus is interrupted, however, by that single bar of 3/4. As we observed in the analysis of Black Moon, Lilith, the swung dotted quarter-note rhythm has a durational ratio of 5:4 which, when fast enough and without the context to give it a swing feel, can be interpreted by a listener as a 1:1 isochronous rhythm. If this is the case here, we could posit that the tactus changes briefly to 68 BPM. But does the listener even have time to register a new tactus? A tactus is formed by interpreting the temporal relations between notes: here the first chord of the 3/4 bar is presumed to follow the previous tactus of 51 BPM. The second chord frustrates this, having esoteric temporal relations to the previous note values, which leaves the listener grasping for a new tactus. The following chord in the 6/8 bar provides another measuring point that confirms the previous two chords as being equal in length and thus candidates for a new beat; however, before this tactus can be established more firmly, the 51 BPM tactus with which the listener is already familiar returns.

This happens again at the transition between the chorus and Verse 2, but this time the two chords of mysterious temporal relations are recontextualised: their rhythm is repeated over the original 102 BPM pulse and the listener can retroactively understand them as swung, even if they heard them as isochronous before.

In the first instance, the two chords function as an interruption of the tactus, a moment out of time. This effect is further achieved by the mix suddenly being stripped back. In the second instance, this moment out of time transforms into a preparation for the return of the verse’s tactus. As with Black Moon, Lilith, the tactus modulated between verse and chorus, giving the impression of slowing down, speeding up, or suspending time altogether.

Here's a live video from the Piehouse show, in which Dave's fantastic drumming demonstrates the tactus modulation from swung 3/4 to half-speed 6/8 a lot more clearly. You can also see me, like a wobbling foal, make an awkward first attempt at engaging frontwomanship, complete with teenagerish voice-breaks... but at least I was having fun!

A lot was made of the concept of "queer time" — and how these songs ostensibly convey the concept musically — in the press material for and subsequent reviews of Pluperfect Mind. You know how it goes: you write something that sounds sort of profound in an accepted press-release tone to legitimise your art in the eyes of... someone. The Big Other? Yeah, it's probably the Big Other. But off-trend queer theory aside, learning about Hannan's theoretical work put a name to the rhythmic stuff I was already instinctively doing, and it's inspired me to continue writing in this vein (though always prioritising songcraft over experimentation for the sake of it, I would like to think). If you've heard any of my new songs live then, first of all, thank you, but you've also had a glimpse of what's in the works...